Museum Archives: The Churchwardens’ Challenges.

There are records made by the churchwardens of St. Andrew’s Church in Steyning going back for centuries. The churchwardens were the guardians of the public parts of the church (the nave, porch and belfry, but not the chancel which was the vicar’s responsibility), the churchyard and any land owned by the Church – plus the silver, the books and the furnishings. All this was done whilst they continued with their own trades and businesses.There were generally two ‘wardens of the churche’. But 500 years ago, in 1521, Roger Burdfold and John Dunstall had six extra wardens to help them with specific duties. ‘John Fawcher and Robert Butt, wardens of the lyght of Sent Peter... and ther remaynyth in the hondys of the seyd John and Robert viis. viiid [seven shillings and eight pence]’. ‘The same day came Roger Burdfold, John Bode and Wyllyam Parsons, wardens of the kyng ale... and the whole money was delyvryd unto the Brethren wardens, they being Wyllyam Pellet and John Godfrey’.

This needs a bit of explanation. The wardens of the light of St. Peter collected money for wax tapers to be lit on an altar dedicated to St. Peter, within the Church, on the occasion of his feast day. The ‘Kyng Ale’ was a strong ale brewed under the auspices of the ‘Kyng Ale’ wardens at Epiphany which, in 1521, raised ‘xxxiiiiis. xd.’ A contemporary account confirmed its fund-raising potential ‘when this nippitation, this huffecappe, this nectar of life is set abroach,’ it says ‘well is he who can get the soonest to it and spend the most at it, for he is counted the godliest man of all the rest’. The ‘brethren wardens’ looked after the interests of the Brotherhood of the Holy Trinity, the owners of Brotherhood Hall in Church Street.

Fund raising apart the churchwardens could have tricky situations to sort out. The two church wardens had to report (or ‘present’) any matters of importance to the Archdeacon or Bishop, reports which were then recorded in ‘The Book of Presentments’.

For instance, in 1571 they named 16 people who had failed to attend holy communion during the previous year. Some of these would undoubtedly have been Catholics such as John Leedes, a gentleman from Wappingthorne, and his wife. Others were of more modest means – there were two tailors and a capper amongst them – and their beliefs are not recorded. Richard Adams was singled out for ‘divers faltes for not comynge to the church and denyeth to pay the forfeyture in that behalf made’

Some merely felt that they had better things to do than go to church. ‘Edith Symond did rost a goose and had it spent on Sondaie before service’. The smell of it must have been a give-away.

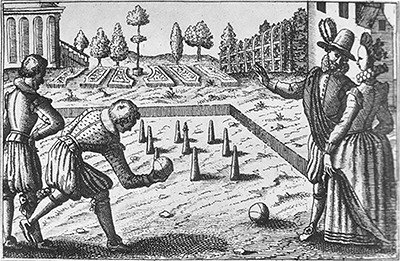

In the same year ‘James Broke was playing at the bowles in the time of divine service and when the churchwardens warned him of his faltes he thretned them and gave them evell languag’. Playing bowls was actually a banned pastime. A Henry VIII statute had forbidden artificers, labourers, apprentices, husbandmen and servants to play bowls at any time except Christmas. Henry’s intention had been to ensure that men should practice with the long bow – in Steyning’s case on ‘Shooting Field’ – rather than play games. That it was on a Sunday that James had played bowls was the ultimate affront. The same insistence on practicing archery meant that, back in 1481, two Steyning men had been taken to court for playing tennis.

Even the churchwardens themselves were fallible. John Stemer, a sidesman who should have been a support to his churchwarden, chose to rat on him: ‘In the evening praier, after the first lesson was don, I went out of the Church to see good rule according to mine oaths and found James Holland, innkeeper, one of ye churchwardens, and Richard Pellet and John Kok drynkyng in ye servis time.’

Tudor England was clearly not an easy time for churchwardens.

Image: Gentlemen playing Bowls in Tudor times.