Museum archives: Steyning’s Church in the 1790’s

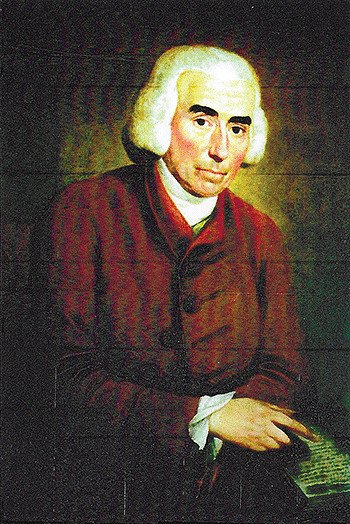

As 28 year old John Penfold looked out over his congregation, in the months following his induction as vicar of Steyning in November 1792, one wonders what would have been going through his mind. Would it have been the condition of the church or maybe the condition and well-being of his flock? Would it have been the state of the nation and Steyning’s role in the nation’s politics? Would his mind have been on the incipient birth of his and his wife Charlotte’s first born, or would he possibly have been deaf to everything other than the noise of the sparrows drowning out his words of wisdom – and the mess their droppings were making in and around the church?The churchwardens (Thomas Groome and John Burfield), certainly, had it in for the sparrows, as we’ve mentioned before. In just three years, they paid out for 620 sparrow heads at 3d. per dozen. But they also had much wider responsibilities for the upkeep of the Church.

They spent money on brooms, variously described as 'heath brooms' (1½d. each), 'hair brooms' (2 shillings each) or just 'brooms' (2d. each), in part for sweeping the churchyard paths between November and Easter (shown to have cost 5 shillings in one snowy year) but also, one supposes, for dealing with those sparrow droppings. ‘Heath brooms’ must have been what we now call besoms but we are not sure what ‘hair brooms’ – possibly soft brooms made using horse hair – would have been used for.

John Brackley, a bricklayer who lived at 94 High Street, and Philip Norris, a mason whose house was next to the Stone House in Singwell Street (now the south-east end of the High Street), were paid for mending the churchyard walls and, in 1796, doing considerable repair work on the West corner of the tower. The roof was also attended to and the churchwardens accounts show that 'the south side of the Parish Church is just new heald' (i.e. re-tiled). This involved '1,667 feet tile healing' which, together with other materials, scaffolding and, of course, beer, cost the considerable sum of £30.4s.5d.

There is also a separate receipt for more work done on the tower by William Welling. His bill for 17 days work for him 'and a boy' came with an entry stating 'beer at ye White Horse and Chequers -11s.4d' That is a lot of pints of beer: whether the 'boy' helped with the drinking of it is not known.

John Penfold must have found the church in a poor state of repair because, in the first few years of his incumbency - apart from the work on the roof and the tower - James Goodyer, a glazier (living at what is now St. Barnabas’ charity shop) was paid for 110 new 'quarries' (i.e. standard sheets of glass) at 1½d. each, 150 lbs of lead in a sheet form at 3d. per lb and 30 feet of lead in strip form at 4d. per foot.

There was also work on the bells, involving yet more Steyning craftsmen. John Morris, the brazier, made a new brass 'gudgeon' (7s. 6d.)(a gudgeon is the seating let into the beam on which the bell rocks), Thomas Cox, a blacksmith, fitted a new chain and screws and nuts to 'ye clipes of a bell' (clappers?), Hugh Kidd, another blacksmith, provided '3 long iron wedges to the bells' and charged 6d. for 'mending the hammer', John Tilley, a grocer, provided the oil to lubricate the mechanism and Richard Shotter, a saddler, supplied a new set of bell ropes (£1 8s). Thomas Cozens undertook the tricky job of re-hanging the bells but also billed the Church for 'mending the floors in the lofts' and putting in a tie beam in the tower.

It is as a result of the work done by these skilled men and many others over the centuries that, despite some periods of neglect, Steyning’s Church has survived and prospered.