Steyning Museum archives: The Steward of the Manor of Steyning

The steward for the Manor of Steyning in 1338 had the Anglo-Norman name of William de Saon. We know this because it appears in the manorial accounts for that year. The year before that Edward III had gone to war with France and had taken control of the English properties of French abbeys and priories. Consequently, when the accounts for the Manor were compiled, based on William’s tallies and records, they were not presented to the Abbey of Fecamp as usual but were submitted to – and preserved by – the crown.William was living at a time when life was uncertain. As a young man, some twenty years earlier, there had been a string of disastrously wet and cold summers leading to the failure of one harvest after another, causing famine and death. Whether he also survived the Black Death which swept the country just ten years later we don’t know. The chances were not good as Steyning, along with the rest of the country, would probably have lost at least a third of their men, women and children to the plague.

What was Steyning like when William de Saon lived here? When he walked to Church each Sunday and on saint’s days he would have seen a building which was somewhat different from the one we know now. The chancel was bigger, there was no large porch and the tower was in the middle, rather than at the end, of the Church. But, once inside, he would have seen the same columns and arches in the nave that we are familiar with today. However, as the walls were painted with scenes from the bible and candles burnt in side chapels dedicated to particular saints – Cuthman among them in all probability – it would have felt vastly different.

William may have been aware that boats used to sail up the river to Steyning, perhaps being beached just to the north of the Church, but this no longer happened in 1338: the river had silted up long before.

Walking up towards the High Street from the Church, William would have passed small cottages, each in their own plots – though, on the evidence of limited archaeology, the settlement does not seem to have been continuous. There were also some dwellings down both sides of the High Street, but none of those which William passed have survived unchanged: the attractive buildings which grace the town now were all built later.

Steyning was a relatively wealthy borough. It had fairly recently been given the right to elect two members to parliament and to hold two fairs a year. William would have been active in the running of these fairs which were held in September, after the harvest had been brought in. He would also have been there when the regular markets were held each Wednesday and Saturday. In the absence of shops as we know them, it was in the bustle of the market place that produce was bought and sold.

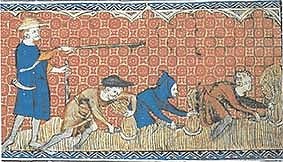

The harvest in 1338 had been a fairly good one and every detail of the crops harvested and the animals kept by the Manor was recorded by William de Saon.

We can see how 5% of all the crops and livestock sold by the manor was creamed off by its lord and how the stewards accounted for every penny. We discover that the skin of a sheep which had died of the “murrain” was sold for a penny, that “a worn-out ox” fetched 3 shillings and that “strewing straw for the lord’s hunter” cost sixpence. Actually many payments were in kind rather than in cash. So a capon was given to “Master Richard” as part of his expenses for attending a sitting of the court and the boy described as “a corn-keeper at seed time” – probably a ‘bird-scarer’ – was paid with barley.

William de Saon went into so much detail about how the Manor was run that we should be able to explore more about Steyning in 1338 in a subsequent article.